Fluid 960 Grid System

6/6 Columns

All images, names and logos used on this page are the trademarks of Wikipedia the free encyclopedia that anyone can edit, and their use or appearance on this website does not constitute any affiliation, endorsement or support.

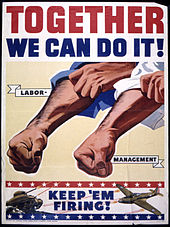

We Can Do It!

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the US government called upon manufacturers to produce greater amounts of war goods. The workplace atmosphere at large factories was often tense because of resentment built up between management and labor unions throughout the 1930s. Directors of companies such as General Motors (GM) sought to minimize past friction and encourage teamwork. In response to a rumored public relations campaign by the United Auto Workers union, GM quickly produced a propaganda poster in 1942 showing both labor and management rolling up their sleeves, aligned toward maintaining a steady rate of war production. The poster read, « Together We Can Do It! » and « Keep ‘Em Firing! »

Rosie the Riveter

During World War II, the « We Can Do It! » poster was not connected to the 1942 song « Rosie the Riveter », nor to the widely seen Norman Rockwell painting called Rosie the Riveter that appeared on the cover of the Memorial Day issue of the Saturday Evening Post, May 29, 1943. The Westinghouse poster was not associated with any of the women nicknamed « Rosie » who came forward to promote women working for war production on the home front. Rather, after being displayed for two weeks in February 1943 to some Westinghouse factory workers, it disappeared for nearly four decades. Other « Rosie » images prevailed, often photographs of actual workers. The Office of War Information geared up for a massive nationwide advertising campaign to sell the war, but « We Can Do It! » was not part of it.

A propaganda poster from 1942 encouraging unity between labor and management of GM

Ed Reis, a volunteer historian for Westinghouse, noted that the original image was not shown to female riveters during the war, so the recent association with « Rosie the Riveter » was unjustified. Rather, it was targeted at women who were making helmet liners out of Micarta.

4/4/4 Columns

Westinghouse Electric

In 1942, Pittsburgh artist J. Howard Miller was hired by Westinghouse Electric’s internal War Production Coordinating Committee, through an advertising agency, to create a series of posters to display to the company’s workers. The intent of the poster project was to raise worker morale, to reduce absenteeism, to direct workers’ questions to management, and to lower the likelihood of labor unrest or a factory strike. Each of the more than 42 posters designed by Miller was displayed in the factory for two weeks, then replaced by the next one in the series. Most of the posters featured men; they emphasized traditional roles for men and women.

No more than 1,800 copies of the 17-by-22-inch (559 by 432 mm) « We Can Do It! » poster were printed. It was not initially seen beyond several Westinghouse factories in East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and the Midwest, where it was scheduled to be displayed for two five-day work weeks. The targeted factories were making plasticized helmet liners impregnated with Micarta, a phenolic resin invented by Westinghouse. Mostly women were employed in this enterprise, which yielded some 13 million helmet liners over the course of the war.

The slogan « We Can Do It! » was probably not interpreted by the factory workers as empowering to women alone; they had been subjected to a series of paternalistic, controlling posters promoting management authority, employee capability and company unity, and the workers would likely have understood the image to mean « Westinghouse Employees Can Do It », all working together. The upbeat image served as gentle propaganda to boost employee morale and keep production from lagging. The pictured red, white and blue clothing was a subtle call to patriotism, one of the frequent tactics of corporate war production committees.

3/3/3/3 Columns

Miller is believed by many to have based the « We Can Do It! » poster on a monochrome United Press International (UPI) photograph taken of Ann Arbor, Michigan, factory worker Geraldine Hoff in early 1942 when she was 17.The photograph of Hoff shows her wearing a polka-dotted bandana on her head, standing up and leaning over a metal-stamping machine, and operating it with her hands at thigh level firmly on the controls.

Hoff left her factory job soon after the publicity photograph was taken; she heard that the metal-stamping machine had injured the hand of the previous operator, and she did not want to ruin her ability to play the cello. She obtained a new job as a timekeeper for another factory. If Miller was inspired by the UPI photograph at all, he freely re-interpreted it to create the poster, putting Hoff’s right hand up in a clenched fist, her left hand rolling up the right sleeve.

Miller turned Hoff’s head to face the viewer, and made her more muscular. He also put a Westinghouse employee identification badge on her collar. Hoff knew nothing of this; she was unaware that Miller was making a poster. She married in 1943 to become Geraldine Doyle. Westinghouse historian Charles A. Ruch, a Pittsburgh resident who had been friends with J. Howard Miller, said that he doubted Doyle’s connection to the image.

He said Miller was not in the habit of working from photographs, but rather live models. Penny Coleman, the author of Rosie the Riveter: Women working on the home front in World War II, said that she and Ruch could not determine whether the UPI photo of Doyle had appeared in any of the periodicals that Miller would have seen. In subsequent years, the poster was re-appropriated to promote feminism. Feminists saw in the image an embodiment of female empowerment.

7/5 Columns

Rediscovery

In 1982, Doyle saw the « We Can Do It! » poster reproduced in a magazine article, possibly « Poster Art for Patriotism’s Sake », a Washington Post Magazine article about posters in the collection of the National Archives. Doyle immediately recognized it as an image of herself, though she had never seen it before. In subsequent years, the poster was re-appropriated to promote feminism. Feminists saw in the image an embodiment of female empowerment. The « We » was understood to mean « We Women », uniting all women in a sisterhood fighting against gender inequality. This was very different from the poster’s 1943 use to control employees and to discourage labor unrest.Smithsonian magazine put the image on its cover in March 1994, to invite the viewer to read a featured article about wartime posters. The US Postal Service created a 33¢ stamp in February 1999 based on the image, with the added words « Women Support War Effort ». A Westinghouse poster from 1943 was put on display at the National Museum of American History, part of the exhibit showing items from the 1930s and ’40s.

Legacy

Another poster by J. Howard Miller from the same series as “We Can Do It!”

After Julia Gillard became the first female prime minister of Australia in June 2010, a Melbourne street artist calling himself Phoenix pasted Gillard’s face into a new monochrome version of the « We Can Do It! » poster. Another Magazine published a photograph of the poster taken on Hosier Lane, Melbourne, in July 2010, showing that the original « War Production Co-ordinating Committee » mark in the lower right had been replaced with a URL pointing to Phoenix’s Flickr photostream.

8/4 Columns

In March 2011, Phoenix produced a color version which stated « She Did It! » in the lower right,[32] then in January 2012 he pasted « Too Sad » diagonally across the poster to represent his disappointment with developments in Australian politics.

A stereoscopic (3D) image of « We Can Do It! » was created for the closing credits of the 2011 superhero film Captain America: The First Avenger. The image served as the background for the title card of English actress Hayley Atwell.